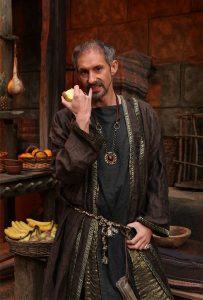

Politicians ancient and modern in the comedy series Plebs

Note: For the module ‘Classics in Popular Culture’ (CLC315), students were asked to write blog posts on Classical Reception in the TV series Plebs or Once Upon a Time, and on the comics Asterix or George O’Connor’s Olympians. Some of the best blogs are featured on our departmental blog site. (Please note political views are the student’s, not necessarily the department’s.)

A striking result from a class quiz result got me thinking about the political message in the comedy series Plebs. Asked whether we agree that the series is ‘purely for entertainment’, the vast majority of us, including myself, answered in the affirmative. On reflection, though, I think I answered like this because of the show’s close similarity to The Inbetweeners – a sitcom about a dysfunctional group of lads, outsiders to the society they live in, who are thrown together into outrageous situations. But I have now come to the conclusion that underlying the comedy of Plebs is a political message. Tom Basden, a writer on the show, admits that the ‘Plebgate’ scandal in politics, featuring a clash between an MP and the police, at the time of the show’s initial release highlighted a key theme: that people are the same now as they were two thousand years ago. He explains that there is always going to be the angry mob ready to criticise the rich and powerful; and that society will always be obsessed with class.[1] So, with this in mind I am interested in Plebs’ use of Classics and modern politics.

Politicians

We all know that politicians are basically untrustworthy. Nigel Farage exemplifies this, for example in his promise that there would be £350 million for the NHS once we voted for Brexit. In Plebs, there is no greater archetype for the untrustworthy politician than Victor in the episode on The Candidate. He is clearly depicted as the ‘conservative’ candidate for the election week. He hires ‘clappers’ (people to support his campaign trail) and wears a Donald Trump type toupee. What is more worrying is that he has no idea about the common people. When visiting a poorer district, the Aventine, Victor declares that the people would like a “biscuit based brawl”. This is a clear dig at our out of touch politicians, such as Ed Miliband who guessed that a weekly shop for a family of four would be £70 or £80, which is £30 short of the national average.[2] Even though his representation is exaggerated, Victor’s cluelessness about the Aventine does seem to be plausible because there was no real ‘middle class’ in Ancient Rome.

Julius Priscus, who represents the opposition, is also worth a mention. He has laudable socialist ideas about renewing the Aventine and stopping corrupt landlords. Ironically, at the end of the episode, the game of politics seems to have changed him. He wins the campaign, but only with the support of the landlords he so desperately wanted to get rid of. Grumio dubs him a “slippery sod”, and I must say, on the whole, that this is the prevailing feeling about all politicians by the end of this episode.

“A tiny cog in a big wheel”

Key targets for satire are ‘the landlords’, a mafia-esque consortium, working together to keep themselves rich and the poor, even poorer. As Landlord states, as he raises Marcus and Stylax’s rent, “I’m just a tiny cog in a big wheel”. But this does not ring true for the rest of the episode. In fact, Landlord has a sinister hold over the politics in Rome and ultimately Davus, his henchman, assassinates Victor. Earlier in the episode the group of landlords have an informal meeting with Victor at the baths, ominously remarking: “we think you’ve forgotten who your friends are.” The parallel between the personal relationship between endorser and endorsee, common in modern politics, is difficult to miss: in the Tory party, reportedly, the highest donation from an individual was from the businessman, Michael Farmer, who is also co-treasurer of the Tory party.[3] It seems that manipulation in politics has been true throughout time, and scholars such as Staveley explore how voting was rigged in Rome.[4] It occurs to me that the disparity between the classes is really apparent in the context of Plebs. The show uses this to highlight the failings of our own politicians.

Marcus climbs the social ladder, becoming a ‘wigman’ cum political advisor to Victor’s campaign. He suggests a cap on rent in the Aventine to Victor; and in desperation for the crowd’s applause Victor supports it and Marcus’ and Landlord’s roles are then reversed. This is displayed perfectly when Marcus delivers the line back to Landlord: “I am just a ting cog in a big wheel”. Reversal of class is something we also witness in the episode Jugball, when Marcus takes on Flavia’s job. Both times though, the role reversal is restored as Victor is assassinated and Flavia becomes manager again. By the end of The Candidate and Jugball the main characters in fact end up in a poorer position than they were previously, and in The Candidate, Aurelius informs the gang that they will be fined if they do not clap at political speeches.

On the whole, Plebs criticizes the corruption that surrounds politics, the way in which it is used as a game simply to be won. It undermines the two main modern ideologies of Labour and Conservative by displaying the representatives, Victor or Julius Priscus, as easily bought. Nothing changes at the end of the episode; there is no revolution of the people, no fair representation for the Aventine. The status quo remains the same, and there is a feeling that history repeats itself. And, I must say, a similar feeling comes every five years after an election.

Written by Rebecca Elms

[1] Basden, T (2013) ‘Plebs: A funny thing happened on the way to the Colosseum’, The Independent, http://www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/comedy/features/plebs-a-funny-thing-happened-on-the-way-to-the-colosseum-8547754.html. Accessed: 26/10/2016/.

[2] Graham, G. (2014). ‘Ed Miliband’s weekly shopping bill? Er… £70? More?’, The Telegraph. http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/politics/ed-miliband/10842953/Ed-Milibands-weekly-shopping-bill-Er…-70-More.html. Accessed: 27/10/2016

[3] Thelwell, E. ‘FactCheck: party donors—who funds Labour and the Tories’, http://blogs.channel4.com/factcheck/labour-funding-party-donors-tories-factcheck/13899 . Accessed: 27/10/2016

[4] Staveley, E. (1972) Greece and Roman Voting and Elections. London: Thames and Hudson.