Chocolate, death, and St Valentine

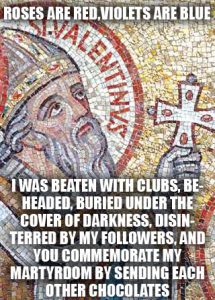

You’ve probably all seen the St Valentine’s meme on social media:

(Image from: http://blog.cnbeyer.com/history/will-the-real-st-valentine-please-stand-up-or-why-i-hate-the-history-channel/)

It is a pretty good joke, pointing out the incongruity of celebrating the violent death of an early Christian martyr at Rome with a consumerist frenzy dedicated to love and romance. Moreover, the meme is quite well-informed: the basic outlines of the story derive from an anonymous Latin account of Valentine’s torture and death.

Of course, the whole story is pretty dubious. The text itself is late, dating to the sixth or seventh century, and so to some 200-300 years after the Romans had stopped persecuting Christians. Many of the details it contains push the limits of historical credibility. The persecution in which Valentine supposedly died happened “during the reign of Claudius” but it is not clear which Claudius is meant: the Julio-Claudian emperor Claudius (AD 41-54) is too early, given that Roman persecution of Christians didn’t begin until the reign of his successor Nero; and the later emperor Claudius II (268-270) is not known to have suppressed Christians. The historical situation is confused further by the text’s mention that Valentine was a priest at Rome when the pope was Callistus, whose dates of 217-222 coincide with the reign of neither emperor Claudius. If you like your history full of “accurate facts”, this story will have you pulling your hair out.

But that is probably to approach the text about Valentine in the wrong way. It was never meant as straight history, but rather as a celebration of a Roman saint and martyr. In fact, it is one of dozens of Latin romances about martyrs composed at Rome between the fifth and seventh centuries. These texts reflect the popularity of martyr cult, and were themselves so popular that their use in Christian services had to be restricted by the Church.

The Valentine story shares many features with these other romances – and not just a cavalier attitude to historical “accuracy”. The scenes of Valentine curing a magistrate’s daughter of blindness, of his subsequent arrest, torture, and death, as well as of the recovery of his body by a Christian matron who then buries it in a Christian cemetery – all of these are features that can be found in countless Roman martyr romances. Moreover, the story of Valentine appears in a connected narrative that contains the stories of other martyrs too, such as the Persian pilgrims Marius, Martha, Audifax, and Abbacuc who came to Rome to visit the tombs of the martyrs and ended up as martyrs themselves.

In other words, the story makes perfect sense in the context of Christian Rome in Late Antiquity. This was a time when the flourishing cult of martyrs created a demand for stories to explain who these martyrs were. These stories often papered over cracks and uncertainties in the historical record, or simply invented details where none survived. For example, from a calendar of saints’ days that dates to the same period as the story of Valentine, we learn that 14 February was associated with not one but two martyrs called Valentine: one from Rome, and the other from Interamna, modern Terni in Umbria, but confusingly buried at Rome. (And there are other Valentines besides: the name was relatively common.) Were these two Valentines the same person? Scholars usually assume that they were, but disagree on which came first. In any case, the story told in the martyr romance about Valentine is plainly the Roman one mentioned in the calendar. It records that he was buried on 14 February at the Via Flaminia leading north from Rome, where a church dedicated in Valentine’s name is known from the fourth century. (Barely anything remains there anymore, although a skull allegedly belonging to a St Valentine is now on display in the church of Santa Maria in Cosmedin in the centre of Rome.) And that is essentially what the story is all about: an explanation of how a Valentine celebrated on 14 February ended up buried on the Via Flaminia, and to which various details of his heroic Christian resolve in the face of persecution have been added.

So did St Valentine suffer as horribly as the meme suggests? Probably not: the story was invented to tell a compelling and inspiring story to a receptive audience. But then he has nothing to do with the celebration of romantic love either: that association seems to have come about only in the later Middle Ages. So far as St Valentine is concerned, Tina Turner got it absolutely right when she sang: “What’s love got to do with it? What’s love but a second hand emotion?”

In other words, you can send each other chocolates, and gobble them up too, with a clear conscience.

Written by Prof. Mark Humphries