Charon doesn’t have a great job, but he Styx with it – the representation of Charon in O’Connor’s graphic novel ‘Hades’

Note: For the module ‘Classics in Popular Culture’ (CLC315), students were asked to write blog posts on Classical Reception in the TV series Plebs or Once Upon a Time, and on the comics Asterix or George O’Connor’s Olympians. Some of the best blogs are featured on our departmental blog site.

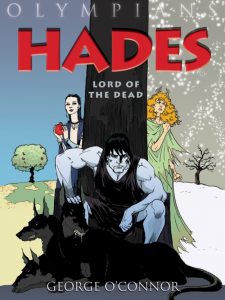

I’ve always been a fan of comic books and graphic novels and was surprised to find that someone had created a series about the Greek gods. Finding out that the target audience of the Olympians was young children I was worried that I would not be able to fully enjoy them; how wrong I was! After reading Zeus I decided to read Hades as I view Hades as the most underrated Greek god. I call him a Greek god instead of an Olympian because just as O’Connor says in his author’s note that ‘He cheated. Hades is not an Olympian.’ That being said I had expectations before sitting down to read Hades of a quite morbid and dark visual novel and my expectations were fully met by O’Connor.

At its core the Hades novel’s primary purpose is to teach its reader about how Hades came to be married to Persephone. But any piece of work writing about death and the underworld contains deeper meanings. O’Connor chooses to describe the journey into the underworld as if it were you yourself embarking on the journey. This not only allows him to fit as much information about the underworld as possible in a short period of time, but also allows him to touch on much more existential meanings

At its core the Hades novel’s primary purpose is to teach its reader about how Hades came to be married to Persephone. But any piece of work writing about death and the underworld contains deeper meanings. O’Connor chooses to describe the journey into the underworld as if it were you yourself embarking on the journey. This not only allows him to fit as much information about the underworld as possible in a short period of time, but also allows him to touch on much more existential meanings

The Hardworking Ferryman

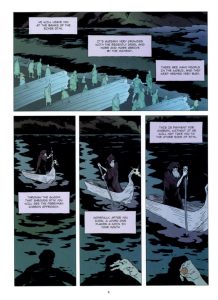

The ferryman Charon is one of the staples of the Underworld in the ancient world. He did not have to be included in this visual novel as O’Connor’s focus is primarily on the Olympians. However O’Connor has him appear in 8 panels throughout Hades with most of these appearing at the start of the visual novel. We can say that by including Charon at the start of Hades, O’Connor bases the structure of this graphic novel on the journey a dead person would take as they enter the underworld. Charon also acts as O’Connor’s ‘tour guide’ as he ferries the soul past all the noticeable criminals in the underworld allowing O’Connor to describe them to his reader.

Sullivan sums up Charon’s depiction in Greek literature as ‘the busy, impatient ferryman, anxious to get the shades aboard’.[1] It is important to look at the depiction of Charon in Greek literature as O’Connor himself revealed he used Hesiod’s Theogony as a model for his Zeus. Euripides mentions Charon in his Alcestis as Alcestis says ‘the ferryman of the dead, Charon, has his hand on the quant and calls to me now: “Why delay? Hurry! You’re holding me up”.[2] This is further evidence of O’Connor taking his model of Charon from Greek literature, much in the same way he modelled Zeus on his representation in the Theogony. O’Connor has clearly gone to great lengths to create an authentic depiction of his characters, even minor ones such as Charon.

Charon as the grim reaper: O’Connor’s hybrid ferryman

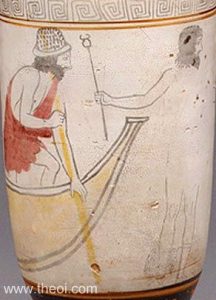

Figure 1: Charon and Hermes Psychopomp, Athenian red-figure lekythos C5th B.C., Metropolitan Museum of Art

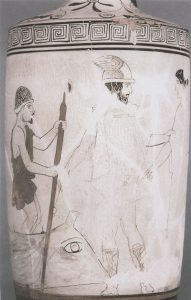

Figure 2: Detail from Athenian red-figure white-ground clay vase circa 450-400 BC. Munich, Antikensammlungen 2777. © Antikensammlungen, Munich

Looking at these two images we can see that O’Connor’s inspiration for his Charon was not just limited to literary descriptions as there were many vases depicting Charon. Sullivan speaks about this saying that Charon was ‘glorified in Greek art’ often depicted with Hermes guiding the soul of the dead.[3] This means that O’Connor had many ancient literary and visual depictions of Charon as a base model. But we can see a break from the ancient visual depiction of Charon as when looking at his clothing in O’Connor’s Hades we see a very dark and cloaked old man. The vases above show Charon as wearing a tunic that barely covers his body whilst also looking more approachable to the dead person he is ferrying across. What O’Connor has clearly done here is move away from the Charon of the ancient world. Instead he creates a hybrid of the modern interpretation of the Grim Reaper with the dark cloak and the animal skull on the front of his boat. Neither of these elements is present on the Greek vases.

Importance of the Coin

The coin to pay the ferryman is a very prominent concept that is found in many literary works. The most notable of these are Book 6 of Virgil’s Aeneid, and the story of Cupid and Psyche from Apuleius’ Metamorphoses.[4][5] Stevens speaks of the custom of putting a coin in a deceased person’s mouth as being found in Greek and Latin literature from 5th Century BC to 2nd Century AD.[6] At first glance it is just a simple coin but Stevens writes that ‘the low value of the coin is a symbol of the poverty of death’.[7] What this can also mean is that no matter how rich or poor you are when you die, it is the same low amount of money that lets you pass on.

Coinciding with this, when looking at the picture to the right, O’Connor writes that ‘hopefully a loved one placed a coin in your mouth’. This at first glance can mean that you physically cannot put the coin in your mouth when you’re dead, which is true. However it has much more weight behind it in a modern view, as you are made to think about your own family and loved ones. They are the ones who decide what happens to you when you die, such as what coffin you have and whether you are buried or cremated.

What I personally take from this comic is that when we die we are all worth the same value, except to your family and loved ones who will mourn your loss. This is emphasised by the comic itself as Hades no longer wants to be alone in the underworld.

Written by Adam Smith

[1] Sullivan, F. A (1950) ‘Charon, the Ferryman of the Dead’, Classical Journal, 46.1, 12.

[2] Euripides Alcestis 252-63.

[3] Sullivan, F. A (1950) ‘Charon, the Ferryman of the Dead’, Classical Journal, 46.1. p.12.

[4] Virgil Aeneid 6.299-317.

[5] Apuleius Metamorphoses, 6.18.

[6] Stevens, S.T. (1991) ‘Charon’s Obol and Other Coins in Ancient Funerary Practice’, Phoenix, 45.3, 215.

[7] Stevens, S.T. (1991) ‘Charon’s Obol and Other Coins in Ancient Funerary Practice’, Phoenix, 45.3, 219-220.