The devil you thought you knew: Hades in Once Upon a Time

Note: For the module ‘Classics in Popular Culture’ (CLC315), students were asked to write blog posts on Classical Reception in the TV series Plebs or Once Upon a Time, and on the comics Asterix or George O’Connor’s Olympians. Some of the best blogs are featured on our departmental blog site.

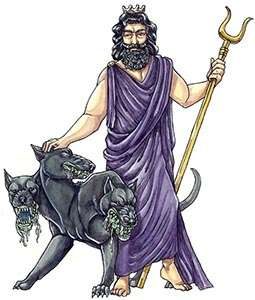

Greek mythology has a tendency to be misrepresented, as apparently ‘many of its heroes transfer very badly to the screen…even Homer proves surprisingly intractable as Hollywood material’.[1] Deviations of the original myths thus abound[2]. There is one figure however, who has (literally) been demonised over the centuries to the point that he is often associated with the Judeo-Christian devil and his area of influence with notions of hell. This figure is, of course, Hades.

See the difference?

Hades, as the Greeks knew him, was the brother of Zeus and Poseidon, and ruled over the Underworld, the realm of the dead. I could list multiple instances in popular culture where Hades is portrayed in a devilish light, but instead I will limit myself to a few episodes of the fantasy series Once Upon a Time (OUAT), in which several fairy-tale characters go to the Underworld to bring back Captain Hook, and find themselves opposed by Hades. This depiction of Hades is based on that of the Disney children’s film Hercules.

The first episode of interest is ‘The Brothers Jones’, which shows Hades making a deal with Captain Hook’s brother Liam, to allow the ship they are on to sink and the crew to die, in exchange for the lives of Liam and his brother. This does not reflect the actual myths and beliefs about Hades held by the Greeks, as there are no myths involving him orchestrating events that lead to the deaths of humans. The only myth where he makes any sort of deal with a human is when Orpheus asks Hades to allow him to take his wife Eurydice back to the land of the living. This request backfires but only because Orpheus himself broke the terms of the agreement by looking behind him. In any event, Hades would have lost nothing if Orpheus had not looked back, as everyone went to him when they died. The OUAT version of Hades, however, appears to want the souls of mortals and he is angered whenever people attempt to escape the Underworld (to the point of beating Hook bloody in an earlier episode). It is even stated by Hook that Hades prevents people from going to a better place: “Hades has the game rigged so no one can leave. My brother’s proof of that. Never did a bad thing in his life”. To compound this seemingly diabolic image, when Hades reveals his non-human nature (picture 4 above), Liam reacts by crying out “You’re a demon!” to which Hades responds “Technically I’m a god, but a lot of people make that mistake”. Hades does make a good antagonist in this episode, as when Hook escapes Hades’ prison and Liam stands up for him, Hades attempts to throw them both into a fiery pit that is said to lead to a place worse than the Underworld (a really subtle allusion to hell).

But there is some justification in ancient literature for such depictions of Hades. In the Iliad, Hades is referred to as ‘of all gods most hated by men’[8] and ‘loathsome’[9]. There is also his portrayal in Ovid’s Metamorphoses, when the author recounts his abduction of Proserpina (Persephone) thus: ‘Proserpina desperately cried for her mother and friends…poor innocent girl! Her abductor was off in his chariot, urging the horses forward’[10]. While these do make Hades appear malevolent, they are to be expected, given the innate human fear of death, as he was feared to the extent that even mentioning his name was avoided. But, many other gods tormented humans and abducted or forced themselves on women, and far more frequently than Hades did!

A more sympathetic version of Hades does appear in the episode immediately after ‘The Brothers Jones’, ‘Our Decay’, in which we witness the first meeting of Hades and Zelena/The Wicked Witch. In this episode, Hades and Zelena bond over their shared dislike for their siblings, in Hades’ case for his brother Zeus. Hades declares that “[Zeus] got everything he ever wanted…while I’m trapped ruling the Underworld…Love, happiness, joy, they’ve all been taken from me”. He goes on to state that he plans to overthrow his brother someday, and wants Zelena’s help to do it. This depicts Hades as someone who became what he is due to feelings of being treated unfairly by his family, resulting in him lashing out at the rest of the world. This bond with Zelena blossoms into romance, showing not only that Hades is capable of love, but also that he is someone capable of being loved. This is a sentiment echoed in a poem from the Late 1800’s, As Persephone tells us “I knew no terror while the God o’ershadowed me…My mother came too late to seek me. She had power to raise life from out Death’s grasp, but from the arms of Love she might not take me, nor undo Love’s past for all her strength’.[11] This poem, while not a classical work, does show that the idea of someone loving Hades is not a recent development. As for him loving someone, Ovid tells us that the abduction of Persephone was motived by love, albeit love brought on by a mischievous Cupid: ‘no sooner espied than he loved her and swept her away’[12]. Hades is presented more accurately in ‘Our Decay’ than in most depictions. It even points out that he is not demonic when, in response to the Wicked Witch asking if ‘the Devil’ is flirting with her, Hades responds, “I’m not the Devil. People are always conflating us”. This is itself a critique of most of his depictions.

In conclusion, this version of Hades is multifaceted, and not entirely inaccurate. While it does perpetuate the image of Hades as a malevolent figure, it does have some classical basis, and depicts him as having some positive characteristics as well. All of which forms a rather interesting character and a successful villain.

Written by Charlie Wade

[1] Nisbet. G., (2006), Ancient Greece in Film and Popular Culture, Exeter: Bristol Phoenix Press, 18

[2] See also: C. Martindale, & Thomas, R (eds.) (2003) Classics and the Uses of Reception, Oxford: Blackwell Publishers

[3] Statue of Hades and Cerberus, Archaeological Museum of Crete. Image sourced from ancient.eu

[4] Image of Hades in Percy Jackson and The Lightning Thief (2010 film). Image sourced from riordan.wikia.com/wiki/Hades

[5] Modern illustration sourced from www.greekmythology.com

[6] Image sourced from disneywikia.com/wiki/Hades

[7] Image of Hades sourced from buddytv.com: 12 Emotional and Unsettling Moments from the 100th Episode of ‘Once Upon a Time’

[8] Homer, Iliad; trans. M. Hammond (1987), London: Penguin Books, 137

[9] Homer, Iliad; trans. M. Hammond (1987), London: Penguin Books, 127

[10] Ovid, Metamorphoses; trans. D. Raeburn (2004), London: Penguin Books, 193

[11] Morris. L., (1879) The Epic of Hades, London: C. Kegan Paul & Co, 166-168

[12] Ovid, Metamorphoses; trans. D. Raeburn (2004), London: Penguin Books, 193