Creative Assessments: Roman Love Poetry–a report from Dr Ian Goh

If you’re thinking about coming to Swansea for university, you should know that we staff in Classics, Ancient History, and Egyptology have thought carefully about the work we get our students to complete, such that not all our assessments are exams, essays, or overtly critical work (see for instance this object biography). Final-year students doing Ian’s module on ‘Roman Love Poetry’ had the chance before Christmas to do a creative assessment related to a topic which the elegiac poets they were studying had employed, accompanied by 1000-word methodological and self-reflective explanations of their process and its relevance, with reference to numerous items of the modern scholarship on the poetry which they had studied.

- The aim was to give students the chance to express their creative side in finding interesting, unexpected, or eye-catching ways of responding to ancient material.

- We try to foster our students’ adaptability, and their ability to express views and encapsulate information in less traditional ways, which reflects how employers look for passion, flexibility, and flair when hiring.

- Students checked the viability of their proposed creative work with the module convenor, and it should be noted that the quality of the work was not of itself the focus of the marking criteria. This is not, for instance, a visual art degree.

- This non-traditional assessment (which did not represent a summative or capstone project) was intended to help students’ wellbeing, and to foster their engagement with and interest in the material during a time of great stress.

- The comments which follow stem from the analytical points made by the students to justify their work.

Andrew Burrows’s poem in rhyming couplets dealt with the aftermath of an illicit tryst in ways that reflected the ancient ‘adultery mime’ and the many love triangles in the extant literature from the early Roman empire. Here’s an extract:

You watch me dress, still with that smile, No panic on your face, even while Your husband's steps echo on the stairs, Their pace relaxed, unknowing of your affairs. I run to your window, its latch unlocked, I turn back to you, but my path is blocked. You kiss me once, twice, thrice in succession, Oh how we both long for the next session. I fly from your room, the landing is rough, Even as I stand, the pain makes me huff. If only our days didn't end in parting, I limp away, backside smarting. When will we meet next? I already count the days, Yet behind me, a judgemental gaze, I turn in worry of being discovered, But there's only the door: my crime is covered.

Misha Ling-Marriott’s picture depicts the beloved as a witch, or perhaps merely bewitching, both ideas often employed by the poets in question. Every aspect of the picture, from the blank expression to the posture employed, reflects elements of the poetry.

For Freya Ford-Elliott, Cynthia’s plight as it was confided to her diary was all too modern, as this extract from the series provided shows.

Dearest Diarium, my skin creases under streaks of dried salted tears. I feel helpless and raw. Gaslit by my final grief, we departed. No longer does he have sympathy for me. Five years of love, tainted by jealousy, unfaithfulness, anger and wretchedness. No longer can I reach into the tresses of my mind and sift through the memories, searching for the happy ones. No, all have been tainted by his final biting words. Until tomorrow, Cynthia

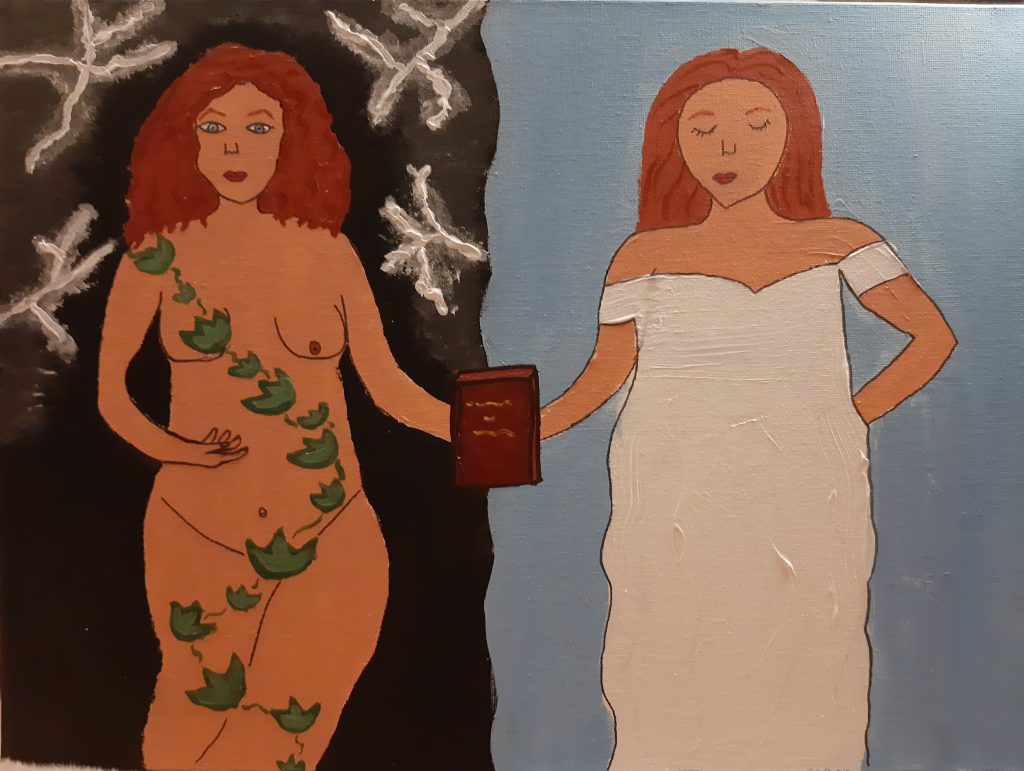

Poppy Taylor’s picture here portrays the divided nature of Propertius’ beloved Cynthia, so often idealised by him (hence the closed eyes and virginal silk dress), but also domineering over the poet-lover despite her vulnerability as symbolised by her near-nakedness. The book in the centre expresses that she only exists as a construct of the written word.