Reflecting on the definition of ‘cultural heritage’

I took Dr Heather Hunter-Crawley’s Greek and Roman Art and Architecture module last year and was taken on an art historical journey, studying the progression of art from Bronze Age Greece to the Byzantine era. One of the ways in which this module was brilliant was the way in which the students were taught how to ‘look’ at art, which isn’t as passive an experience as one may think (similarly to Alastair Sooke’s ‘Treasures of Ancient Greece’, a BBC Production which I highly recommend watching if you are interested in the art history of the ancient world). Heather teaches her students not only the historical significance of sculptures, pottery, and paintings – the Pergamum altar, and the Jockey of Artemision to name a couple of my favourites – but the ways in which they can be read and interpreted. However, while I could easily continue to write about the merits of this module that is not the purpose of this post. Instead I wish to write about a guest lecture given by Dr Nigel Pollard which was organised by Heather at the end of this module.

One focus of Nigel’s lecture was on the Hague Convention in 1954 which passed the Act on the Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict, a law which made it a crime against human rights to damage or destroy a site or cultural or historical importance. The catalyst for this was the extensive damage done to sites during the Second World War, for example Coventry Cathedral or Pompeii. Now, this Act is enforced by groups such as the International Committee of the Blue Shield, which protect sites under threat and seeks to gain the co-operation of governments or other bodies that can help to implement this.

Figure1: Artemision Jockey. National Archaeological Museum, Athens

However, Nigel noted that while this law is commendable, it is not always enforced (of course some sites are easier to protect than others), and there is a global disparity in the definition of ‘cultural heritage’. For example in 2003 the Iraq National Museum in Bagdad was looted as a result of American forces not stepping into the security vacuum after the Taliban were pushed out. Also when comparing the number of UNESCO sites in Europe and Middle Eastern States the difference is quite staggering; 499 and 81 respectively (I use this example as Nigel’s lecture focused predominantly on the Middle East and the West). This to me suggests a dominant interest in Western sites and Western ideas of culture, perhaps at the expense of those elsewhere.

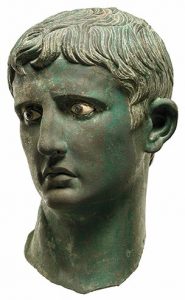

Reflecting back on this lecture I can’t help but notice that in seeking to protect sites of cultural heritage, we are simultaneously potentially making them more vulnerable to cultural conflict. In the past, sites of cultural or historical importance have frequently been targeted by opposition parties as a means to demonstrate another culture’s vulnerability or lack of permanence in the world. In 25/24 BCE the Kushites invaded the province of Egypt (now North Sudan), and in a fit of triumph against Augustus, emperor of Rome, they severed a bronze head of Augustus (see figure 2), which they took back to Meroë and buried under the steps of their victory monument. Not only did this demonstrate resistance to Rome as it was never returned, but this symbolically showed the Kushites’ strength and perhaps cultural superiority over the Roman Empire, and would have evoked a sense of disgust from the Romans (if they knew that this had happened).

With this in mind, it is perhaps not particularly surprising that cultural sites are damaged now, especially with Palmyra in mind (August 2015), and ongoing cultural conflict in the Middle East.

It is noticeable that the West has become increasingly desensitised to the atrocities that have been going on in the Middle East; some may go so far to say as disinterested. Therefore, destroying a place that we have so clearly stated is important to our culture seems an obvious way to attract our attention. Equally though, this Western interest in ancient sites has fuelled the selling of looted antiquities eg. from Apamea. Does that mean that the West is indirectly violating the 1954 Hague Convention?

While I agree that it is important to continue to protect sites with historical importance, I do think that we should be aware that there is a cultural disparity in the consensus in terms of ‘cultural significance’ which may have potentially caused conflict between groups of people. I also would argue that when people set out to protect these sites, it is necessary to be aware that increasing their publicity can have a negative impact. This is a diverse and complex topic, one which ultimately has no ideal solution.

Written by Minette Matthews, 2nd Year Ancient History Student

Here are a couple of links if you are interested in reading more on this:

http://ancbs.org/cms/en/about-us/about-icbs

http://portal.unesco.org/en/ev.php-URL_ID=13637&URL_DO=DO_TOPIC&URL_SECTION=201.html