E Tenebris Lux: Thoughts on the reopening of the Glynn Vivian Gallery

This is a guest blog post by Dr Evelien Bracke, who is currently working on the reception of Classics in Wales.

A month ago, I went along to the reopening of the Glynn Vivian gallery, Swansea’s main art gallery, which had been closed for a £6 million refurbishment since October 2011. It was a lovely event and I felt like a child in a sweet shop exploring the collection.

The gallery was the brain child of Richard Glynn Vivian (1835-1910), who bequeathed his art collection to the city of Swansea, together with £10,000 to create a gallery to house it. The collection is really eclectic: there are such diverse pieces in the permanent collection – from Swansea pottery and Welsh paintings (particularly nice to see a number of female Welsh painters represented), to European and oriental art – that you really get drawn in walking from room to room. Apart from the permanent collection, there is also a temporary exhibit with Leonardo Da Vinci’s drawings which is worthwhile visiting.

An influential family

I was excited to find out that Richard Glynn Vivian, the gallery’s founder, was in fact part of the Vivian family who lived at Singleton Abbey before it became part of the university, about which I have blogged before. The Classical education of the Vivians greets you at Singleton Abbey with a ‘salve’ (‘hello’ in Latin) when you enter the building, and likewise, Classical influences can be found in the Glynn Vivian collection.

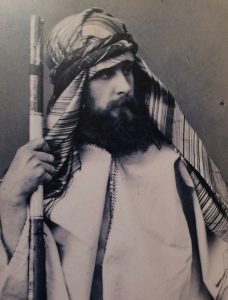

While his older brothers studied science and looked after the family copper smelting business, Richard studied arts at Cambridge and travelled extensively all around the world. By means of his share of the family fortune, he started amassing an extensive art collection during his travels. It must have come as a terrible blow when he started going blind in 1902. He wrote and published a collection of poems (which I’m yet to get my hands on) called E tenebris lux, ‘out of darkness, light’, with the sub-heading ‘scattered leaves gathered together during hours of blindness’.

The Latin title, which refers to Genesis 1.4, expresses the strengthening of his Christian faith – already running deep in the Vivian family, as the Latin quotes on the walls of the council chamber of the Abbey reveal – because of his blindness, and it was to the cause of shining a beacon of light in the darkness of humanity that he dedicated the rest of his life.

Apart from opening the Glynn Vivian gallery which gave access to international art to people from all economic backgrounds in South Wales, he also became a patron of miners – which will have had a profound impact on local communities – through the Glynn Vivian Miners’ Mission and established a home for the blind on Gower. Upon his death, his will further divided his fortune between charities.

Dialogue of past and present

Walking through the gallery, Glynn Vivian’s personal taste and philanthropy really speak to visitors through his collection. While Wales plays the leading role in his collection, Classical influences can also be spotted, at times very obviously, other times in a whisper. The statue of the sleeping Pan by French artist S.J. Brun (1832), given a prominent space on its own between two rooms and cleverly juxtaposed with views of the long glass windows and the Swansea street, is a beautiful example.

Less obvious, tucked away among other pieces, is the Dillwyn pottery with Greek-style red-figure vase paintings, inspired by 18th and 19th century archaeological excavations in Etruria. This pottery stands in similar contrast with the contemporary styles of other vases which surround them.

While the building itself has a Baroque style, its interior – and particularly the neoclassical busts – stand in stark contrast with the (awesomely disturbing) postmodern Matrix-like installation on the ground floor.

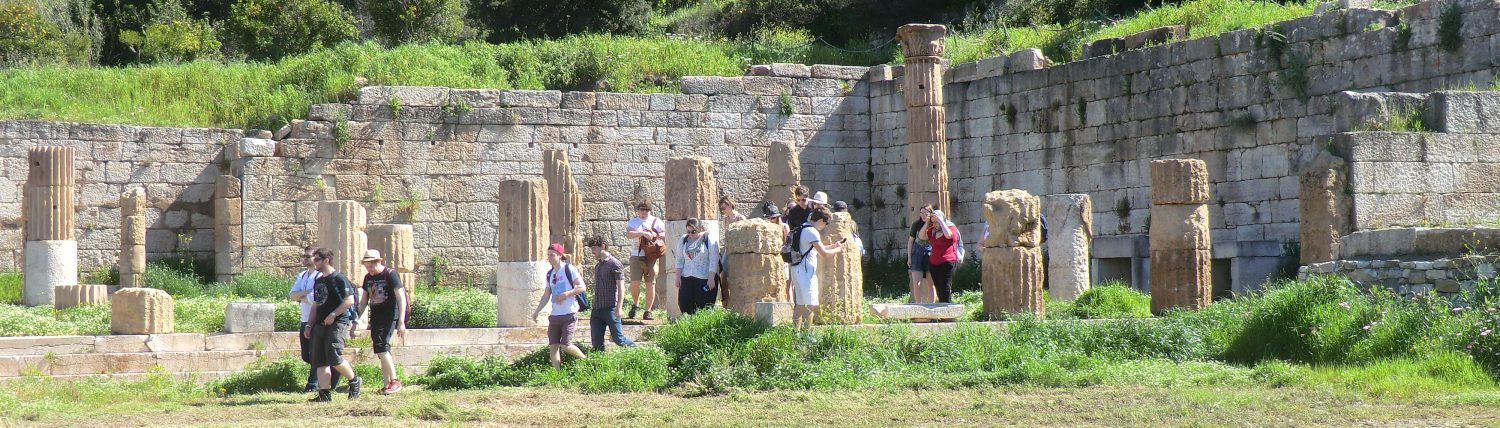

The present curators have obviously created clear boundaries between past and present through their choice of pieces that are very different in style. While they sometimes jar visually, all pieces live harmoniously within the building itself which embraces both its Baroque past and utilitarian extension. I particularly like how part of the building has been opened up onto the street, like a Greek theatre looking out onto the polis while the plays were being staged within.

I can’t wait to go and explore all the pieces further – you might find me sitting in front of the Turner painting for quite a while… In the meantime, though, I’m happy to report that the reopened Glynn Vivian gallery, outward looking and inviting visitors to consider the dialogue – or is it a clash? – between eclectic pasts and present, continues Glynn Vivian’s humanist quest to give everyone access to art and create e tenebris lux!