Classics at Swansea University between copper business and tinplate worker: Ceri Richards’ Rape of Europa

Blog post by Dr Evelien Bracke, Senior Lecturer in Classics, on CLC315 (Classics in Popular Culture).

For my new third-year module, Classics in Popular Culture (CLC315), I decided to take students on a walk through the Singleton Campus, to get them thinking about the ways in which Classics have been appropriated to convey messages about status and ideology in their immediate context.

The walk was a short and straightforward one, along the mall from Singleton Abbey to Fulton House. I have previously blogged about the use of Classics (particularly Latin) in Singleton Abbey. This building, now part of the university, was once the home of the Vivian family who made their fortune from the copper-smelting business.

The contrast with Fulton House, which forms the end of the mall on the other side, could not be starker: juxtaposing the Abbey’s neoclassical abundance, Fulton House earned its Grade II listed status on the basis of its post-war modernist style, designed by architect Percy Thomas. (The students gave Fulton an average of 0/10 for looks.) The building was named after John Fulton, VC of the University of Wales, who had studied Classics at Balliol.

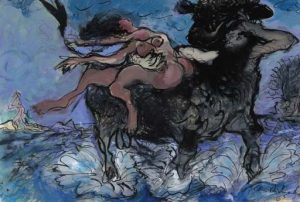

Because of its austere modernism, I had never gone looking for Classical influences in Fulton House – until we had an Open Day in the refectory last summer, and, while I was talking to a prospective student, my gaze suddenly fell upon the large painting of the rape of Europa on the wall. I had never paid attention to it before, even though it has been hiding in plain view since I arrived at Swansea.

The artist is Ceri Richards, born in Dunvant (part of Swansea) in 1903. I can’t but love the way in which his use of Classics contrasts with the wealthy Vivians in the Abbey. Raised in a working class family as the son of a tinplate worker, he was nevertheless brought up surrounded by culture: his mother came from a family of craftsmen, and his father wrote poetry and directed the local choir.

It was in 1921, when Richards went to study at the Swansea College of Art, that he became immersed in Classics while drawing classical casts. A week’s study at Gregynog Hall in mid Wales, the centre for excellence in the arts established by the Davies sisters, must have further sparked his interest (I will write about the Davies sisters in a future blog post).

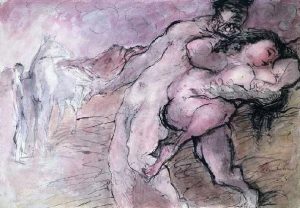

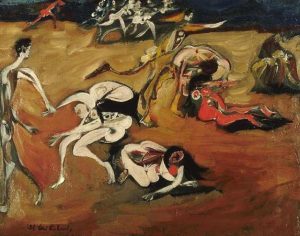

The theme that intrigued him the most, to the point of obsession, in the years 1945-‘49, was the rape of the Sabine women, a well-known story from Roman foundation myth (‘rape’ here signifies ‘abduction’ by the way).

As Livy (Ab Urbe Condita 1.9) narrates, Romulus (Remus’s brother and founder of Rome), unable to find wives for his male followers, tricked the neighbouring Sabines into attending a festival, at which the women were abducted while the men were busy fighting. It is a well-known artistic topos, which has been depicted countless times in art throughout the centuries. To find it in Richards’ repertoire is thus, to a certain extent, not that unusual.

Richards’ wife, Frances, however, says his immediate inspiration came from the force that through the green fuse drives the flower, a poem by fellow Swansea artist Dylan Thomas whom Richards admired greatly. The first two verses give a flavour of the content:

The force that through the green fuse drives the flower

Drives my green age; that blasts the roots of trees

Is my destroyer.

And I am dumb to tell the crooked rose

My youth is bent by the same wintry fever.

The force that drives the water through the rocks

Drives my red blood; that dries the mouthing streams

Turns mine to wax.

And I am dumb to mouth unto my veins

How at the mountain spring the same mouth sucks.

Dylan Thomas’s harrowing poem laments the destructive action of time on nature and mankind. Similarly, as J.R. Webster argues, Richards’ depiction of the Sabine women represented a ‘violent consummation of his wartime preoccupations with birth and death’. The connections between the story of the Sabines and Dylan Thomas might at first seem tenuous: while Thomas’s poem concerns violence enacted by time onto all mankind, Richards focused rather on violence done to women by men. It is unnecessary, however, to look for any logical connection: both pieces reflect on violence through an emotional response and mood rather than logic. Richards thus amalgamated Welsh and Classical influences into one strong image.

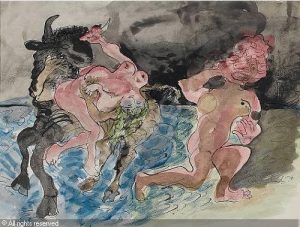

In 1964, Richards was invited to create a painting on a similar theme, the rape of Europa, for the Hotel Europa. Thus he embarked on a series of paintings on that theme, one of which now adorns the Fulton Refectory.

While the Sabine story derives from Roman myth, the story of Europa was ancient Greek in origin: the god Zeus has fallen in love with Europa and had transformed himself into a bull in order to get close to her. Ovid narrates (Metamorphoses 2.833ff.):

And gradually she lost her fear, and he

Offered his breast for her virgin caresses,

His horns for her to wind with chains of flowers

Until the princess dared to mount his back

Her pet bull’s back, unwitting whom she rode.

Then—slowly, slowly down the broad, dry beach—

First in the shallow waves the great god set

His spurious hooves, then sauntered further out

’til in the open sea he bore his prize

Fear filled her heart as, gazing back, she saw

The fast receding sands. Her right hand grasped

A horn, the other lent upon his back

Her fluttering tunic floated in the breeze.

Ultimately, Zeus made Europa queen of Crete, and her name became used for the continent of Europe.

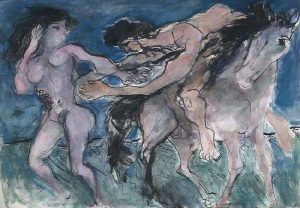

While many post-Classical depictions retain the Ovidian image of Europa holding on to the horn of the bull, Richards’ has her swung back, similarly to the Sabines, held by her waist by the bull/Zeus.

An interesting innovation is that, in each of the paintings, Zeus is in fact taking off a bull-shaped mask, suggesting he had somehow disguised himself rather than transformed, which renders him more human, somehow less capable of divine transformation. One of my students first likened him to a centaur, and it is not unreasonable to discern a centaur-like aspect in his representation. Indeed, the connection between male and horse/bull – present in both rape of the Sabines and rape of Europa – may represent the animalistic aggression by war and time, contrasted starkly with the innocent women, whose accentuated female forms accord with nature. Already in antiquity, both centaurs and (of course) Zeus were depicted as lascivious beyond the norm, violating innocent mortals. Zeus’s representation as part animal, part anthropomorphic, emphasizes the worrying impact of mankind’s animalistic nature on his surroundings.

Ceri Richards’ painting can be interpreted at two levels. First there is Richards’ own use of violent Classical myth in order to cope with and express his feelings about WWII, during which he taught at the Cardiff School of Art. The concept of mankind’s animalistic aggression clearly resonated with him, perhaps – if read through Dylan Thomas’ poem – as random acts against which there is no defense.

A second level of interpretation, however, concerns the context in which the panel was placed (it has apparently been in Fulton House from the moment the building was put to use). The obvious reason is that this was a celebrated Welsh, local artist, whose work deserved displaying. Interestingly, however, the painting also adds an element of Classical heritage to a building which is otherwise devoid of it, thereby connecting Fulton House with the Abbey.

Ideologically, however, the Rape of Europa contains a contradiction: those who decided to display it in Fulton House – perhaps in honour of Fulton’s own study of Classics – did so to lend an air of eminence and status to the building. Richards’ own application of Classics, by contrast, derived from his working-class background, depicting the horrors of war rather than status. In this capacity, the painting by the tinplate worker’s son forms a stark contrast with the Latin mottos adorning the coal-funded Abbey, and invites the viewer to question the links between education, class, and ideology.

At this point in time, moreover, this image takes on a whole new meaning which no one would have anticipated: in Brexit times, the placement of the rape of Europa in a Welsh context suddenly asks poignant and urgent questions regarding identity and ideology. Who might we cast as Zeus now, who as Europa? We were only able to touch upon layers of Classical reception on our walk, so we’ll look forward to discussing these in our next lectures.