Reading Listicles §4: Wherever I may Rome – Ian Goh

Once more into the breach, dear friends, once more! Today I’m giving you, in what’s quickly becoming a pretty personal look at some reading matter you might want to explore before you make it to university, some Roman history tips.

It’s difficult to encapsulate all the comings and goings of Rome and its empire which outdid all previous others in reach and administration, in just one book, which is why (for instance) Mary Beard’s SPQR is so popular; none the less, bear in mind that treatments like that are what we call ‘popular history’: no footnotes or endnotes, just suggestions for further reading at the end.

A magisterial book that sports some endnotes and is available to borrow online is Greg Woolf’s Rome: An Empire’s Story.

If you can afford it, one colleague, Dr Nigel Pollard, recommended a good general introduction, David Potter’s Rome in the Ancient World: From Romulus to Justinian.

There’s also Christopher Kelly’s punchy Very Short Introduction to the Roman Empire.

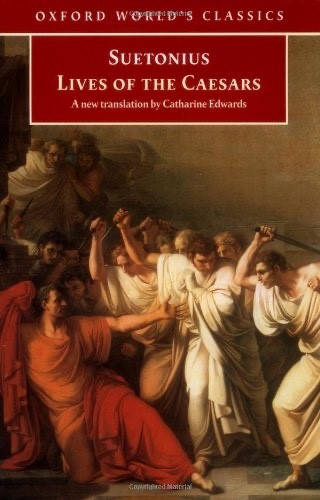

Above all else, though, I would read Suetonius’ Twelve Caesars. Here’s a link to a borrowable translation by Robert Graves, who also wrote I, Claudius. The latter, which became a wonderful TV series—Rome on TV before Rome—is fiction, but very readable and based on Suetonius. Another translation I like of Suetonius is by Catharine Edwards.

More caustic than Suetonius, who is a bit gossip column-y, is Tacitus. His Annals and Histories are available on Lacus Curtius. His work is notoriously difficult to translate but incredible in its insight and throwing of shade. A famous sentence that I love from his Histories is his judgement on Galba, one of Rome’s rulers in the Year of the Four Emperors, AD 69: ‘he was capable of rule, if only he had not been ruler’. Capax imperi nisi imperasset: four Latin words wielded like a dagger. Together they form a hypothetical oxymoron (of course he did actually rule: or did he? Galba spent most of his brief reign riven by indecision and subservient to his bodyguard, the Praetorian Guard, who do him in). But who’s judging him ‘capable’? The citizens he ruled, the soldiers to whom he mistakenly didn’t give a payrise, the senate, Tacitus the authority on ruling (and how would he know)? A lesser author might have written ‘he was capable of ruling until he was ruler’—but Tacitus’ brief summation slyly opens up vistas of interpretation.

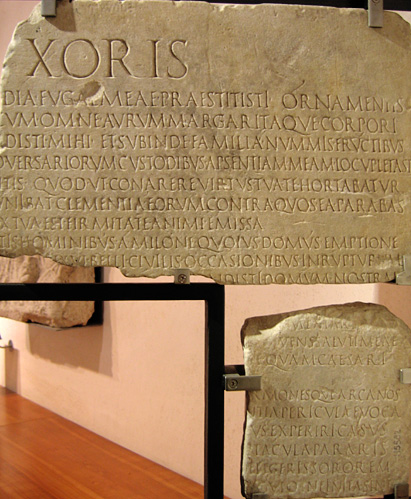

It’s not all pale, male, and stale: my favourite bit of Tacitus is possibly when Nero attempts to kill his mother Agrippina in a collapsing boat at the beginning of Book 14; that book also features another dangerous and powerful woman, Boudicca the British revolutionary. We could contrast those two with some perhaps more tangible evidence of Roman attitudes to women—a key concern of my colleague Dr Jo Berry’s teaching on ancient gender—in an inscription which represents a husband memorialising his dead wife, the ‘Eulogy for Turia’ (the Laudatio Turiae). The text is here

Image source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Laudatio_turiae_2.jpg

What does this enumeration tell us about the place of women in daily life and society? Do you believe everything this grieving husband has committed permanently to the stone above? And speaking of grieving, there’s another classic: on the Via Salaria, a memorial to a gifted and talented kid, Quintus Sulpicius Maximus, who competed in a poetry recitation contest (in the Capitoline Games of AD 94) improvising a poem in Greek on the spot! But he died shortly after aged 11, and his parents set up a tomb on whose monument they put his verses, forever: the memorialising impulse gives them permanence, and it’s stuff like that which Dr Ersin Hussein discusses with you when she runs her module ‘Set in Stone: Inscribing and Writing in Antiquity’. There’s a copy of the monument standing in the Piazza Fiume quite close to where they found it (in the wall of a tower).

Image source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:QS_Maximus_memorial_stone.JPG

What a terrible thing to bury your child: that’s why Mary Beard’s provocative title in this piece on Q. Sulpicius for the BBC is, I think, overcooked.

Come back next week for the answer to the question: how far do we, or should we, go in talking about Rome and talking about ancient things? When does ‘ancient history’ become just plain ‘history’?